CSDS Team with K.C. Suri | Frontline | Nov 06, 1999

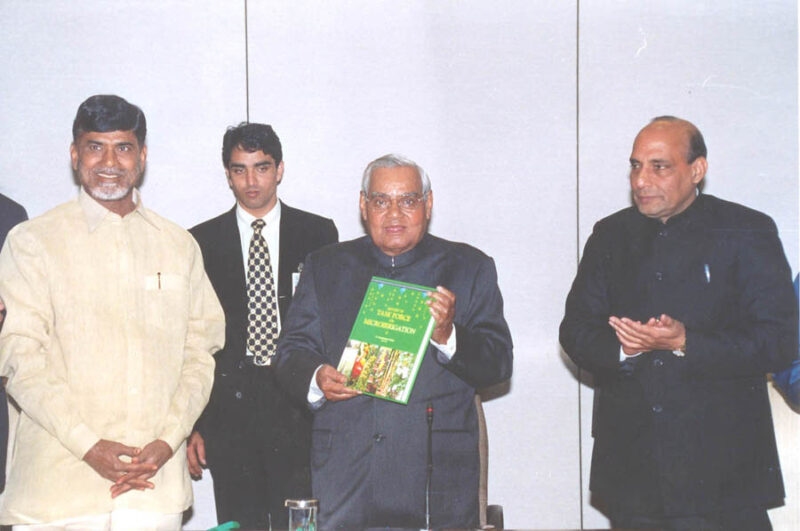

IT is easy to read too much into the victory of the Telugu Desam Party led by N. Chandrababu Naidu in Andhra Pradesh. After all, Chandarababu Naidu can claim to be one of the few undisputed winners of the 1999 elections. As compared to the 1998 elections, his party has increased its vote share and seats tally; to that extent, his visibility and political clout have increased. The TDP under him may not have swept the Assembly elections as it did under N.T. Rama Rao in 1994, but Chandrababu Naidu is one of the few Chief Ministers in recent years to have withstood and triumphed over the tide of anti-incumbency that the media have made much of. The TDP’s tally of 29 Lok Sabha seats made it not only the biggest of the BJP’s allies, but also the fourth largest party in the Lok Sabha.

Yet the TDP’s victory is rather less dramatic when seen in terms of vote share. The vote share of the TDP-BJP combine was only seven percentage points more than the Congress(I)’s vote share in the entire State. The Congress(I)’s vote share in fact went up by over four percentage points as compared to the 1998 parliamentary elections, in which it fared rather well. However, the State witnessed straight contests this time and the spread of votes was relatively even for both the parties; in such a situation, even a small margin translated into an overwhelming victory for the TDP-BJP combine in terms of seats.

This is what made the alliance with the BJP a key factor in the TDP’s success. The BJP’s vote share of 9 per cent this year perhaps understates its role, for it was forced by Chandrababu Naidu, a hard bargainer, to settle for a meagre share of seats. In the 1991 parliamentary elections, the BJP made a big entry in Andhra Pradesh by securing nearly 10 per cent of the popular vote. Its fortunes declined marginally in 1996. It performed well in 1998: it won four parliamentary seats and secured 18 per cent of the popular vote. The TDP’s alliance with the BJP enabled it to more than make up for the losses from the severing of its ties with the Left parties; it also gave the TDP an edge over the Congress(I). The TDP-BJP combine’s vote share (nearly 50 per cent) matches the combined vote share of the TDP and the BJP in 1998. If the BJP had not contested as an ally of the TDP and had fared even half as well as it did in 1998, the TDP might well have faced defeat.

The TDP-BJP combine won comprehensively in all the three regions. Even in Rayalaseema, the last remaining bastion of the Congress(I), the TDP-BJP combine took four seats from the Congress(I) and improved on its vote share over 1998. In Telengana, considered the region where the BJP is the strongest, the TDP-BJP’s combined vote share fell by three percentage points since 1998, but it managed to finish well ahead of the Congress(I). This is the region where the Left parties secured a reasonably good share of the popular vote. This is also the first election since 1984 that the Left parties did not contest as part of a broader alliance, and their performance this time has not been good. In the coastal region, the TDP-BJP combine won all but two seats.

An analysis of the Assembly election results shows that the TDP dominates in almost all the regions. Although the decision to break with the Left parties and team up with the BJP cost the TDP 20 seats in the Telengana region, it retained its hold over coastal Andhra and fared better than the Congress(I) in Rayalaseema. The Left parties suffered the most significant losses this time. The Congress(I) made marginal gains in Telengana and elsewhere, as compared to 1994, when it drew a blank. In all, the TDP retained 141 of the seats it had won in 1994, passed on eight seats to the BJP, and won back 15 from the Left parties, its former allies. The Congress(I) retained only 10 of the 26 seats it had won in 1994, but took 65 from the TDP and 15 from the Left parties.

A carefully crafted alliance and a successful transfer of votes was thus crucial to the TDP’s victory. The CSDS survey data show just how successful the vote transfer from the BJP and the TDP to the new combine was, notwithstanding the dissatisfaction in the State unit of the BJP over the terms of the alliance. In the matter of holding on to its own share of votes in the 1998 elections, the Congress(I)’s performance was the best. It also took away a significant slice of the votes of the BJP and the TDP. The TDP, which retained 85 per cent of its 1998 votes, could not win over many votes from the Congress(I) but it managed to offset its losses by adding 82 per cent of the BJP votes of 1998 to the combine’s votes. It also captured the majority of the votes secured in 1998 by the CPI and the CPI(M), its allies at that time. As in the case of Bihar, excessive dependence on alliances rendered the Left parties vulnerable.

In the Assembly elections, both the TDP-BJP combine and the Congress(I) retained more than 90 per cent of the votes that they secured in the Lok Sabha elections.

Underlying the TDP-BJP’s successful coalition was the forging of a new social coalition of the upper and the middle castes. The addition of BJP votes strengthened the TDP’s position among the upper castes and the peasant OBCs, besides consolidating its traditional Kamma votes. These gains more than compensated for the loss of the votes of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes owing to the break with the Left parties, and of Muslims, who shifted their allegiance to the Congress(I). Even so, the TDP-BJP combine enjoyed more support than the Congress(I) did among adivasis; the TDP’s share of votes of Muslims is one of the highest for any ally of the BJP.

The class profile of the TDP-BJP combine shows an uneasy coming together of the upper classes (who predominantly support the BJP) and the lower classes (who support the TDP). The Congress(I) fared well among the middle class but was squeezed from the upper end by the BJP and the lower end by the TDP. Unlike in Karnataka, the Congress(I) could not reconstruct its base among the poorest sections.

During the campaign, TDP leaders repeatedly claimed that the party enjoyed the overwhelming support of women and young voters. The survey findings do not support this claim. Young voters were equally divided between the TDP and the Congress(I). If anything, the TDP does best among the middle-aged, who perhaps acquired their right to vote about the time the TDP first came to power in dramatic circumstances, in 1983. Similarly, the TDP, which earlier drew a larger share of its support from women than from men, now enjoys about the same proportion of votes across the gender divide. The rural-urban divide does not explain much of the difference, for the TDP enjoys the same lead in both areas. The Left parties have their traditional source of support in the villages.

The survey reveals that as compared to voters in many other parts of the country, voters in Andhra Pradesh are more politicised, more confident, and more attuned to regional politics. At the same time, 75 per cent of TDP voters expressed a preference for A.B. Vajpayee as Prime Minister. About 47 per cent of the voters claimed that they had finalised their voting choice much before the campaign began.

IT is easy to read too much into the victory of the Telugu Desam Party led by N. Chandrababu Naidu in Andhra Pradesh. After all, Chandarababu Naidu can claim to be one of the few undisputed winners of the 1999 elections. As compared to the 1998 elections, his party has increased its vote share and seats tally; to that extent, his visibility and political clout have increased. The TDP under him may not have swept the Assembly elections as it did under N.T. Rama Rao in 1994, but Chandrababu Naidu is one of the few Chief Ministers in recent years to have withstood and triumphed over the tide of anti-incumbency that the media have made much of. The TDP’s tally of 29 Lok Sabha seats made it not only the biggest of the BJP’s allies, but also the fourth largest party in the Lok Sabha.

Yet the TDP’s victory is rather less dramatic when seen in terms of vote share. The vote share of the TDP-BJP combine was only seven percentage points more than the Congress(I)’s vote share in the entire State. The Congress(I)’s vote share in fact went up by over four percentage points as compared to the 1998 parliamentary elections, in which it fared rather well. However, the State witnessed straight contests this time and the spread of votes was relatively even for both the parties; in such a situation, even a small margin translated into an overwhelming victory for the TDP-BJP combine in terms of seats.

This is what made the alliance with the BJP a key factor in the TDP’s success. The BJP’s vote share of 9 per cent this year perhaps understates its role, for it was forced by Chandrababu Naidu, a hard bargainer, to settle for a meagre share of seats. In the 1991 parliamentary elections, the BJP made a big entry in Andhra Pradesh by securing nearly 10 per cent of the popular vote. Its fortunes declined marginally in 1996. It performed well in 1998: it won four parliamentary seats and secured 18 per cent of the popular vote. The TDP’s alliance with the BJP enabled it to more than make up for the losses from the severing of its ties with the Left parties; it also gave the TDP an edge over the Congress(I). The TDP-BJP combine’s vote share (nearly 50 per cent) matches the combined vote share of the TDP and the BJP in 1998. If the BJP had not contested as an ally of the TDP and had fared even half as well as it did in 1998, the TDP might well have faced defeat.

The TDP-BJP combine won comprehensively in all the three regions. Even in Rayalaseema, the last remaining bastion of the Congress(I), the TDP-BJP combine took four seats from the Congress(I) and improved on its vote share over 1998. In Telengana, considered the region where the BJP is the strongest, the TDP-BJP’s combined vote share fell by three percentage points since 1998, but it managed to finish well ahead of the Congress(I). This is the region where the Left parties secured a reasonably good share of the popular vote. This is also the first election since 1984 that the Left parties did not contest as part of a broader alliance, and their performance this time has not been good. In the coastal region, the TDP-BJP combine won all but two seats.

An analysis of the Assembly election results shows that the TDP dominates in almost all the regions. Although the decision to break with the Left parties and team up with the BJP cost the TDP 20 seats in the Telengana region, it retained its hold over coastal Andhra and fared better than the Congress(I) in Rayalaseema. The Left parties suffered the most significant losses this time. The Congress(I) made marginal gains in Telengana and elsewhere, as compared to 1994, when it drew a blank. In all, the TDP retained 141 of the seats it had won in 1994, passed on eight seats to the BJP, and won back 15 from the Left parties, its former allies. The Congress(I) retained only 10 of the 26 seats it had won in 1994, but took 65 from the TDP and 15 from the Left parties.

A carefully crafted alliance and a successful transfer of votes was thus crucial to the TDP’s victory. The CSDS survey data show just how successful the vote transfer from the BJP and the TDP to the new combine was, notwithstanding the dissatisfaction in the State unit of the BJP over the terms of the alliance. In the matter of holding on to its own share of votes in the 1998 elections, the Congress(I)’s performance was the best. It also took away a significant slice of the votes of the BJP and the TDP. The TDP, which retained 85 per cent of its 1998 votes, could not win over many votes from the Congress(I) but it managed to offset its losses by adding 82 per cent of the BJP votes of 1998 to the combine’s votes. It also captured the majority of the votes secured in 1998 by the CPI and the CPI(M), its allies at that time. As in the case of Bihar, excessive dependence on alliances rendered the Left parties vulnerable.

In the Assembly elections, both the TDP-BJP combine and the Congress(I) retained more than 90 per cent of the votes that they secured in the Lok Sabha elections.

Underlying the TDP-BJP’s successful coalition was the forging of a new social coalition of the upper and the middle castes. The addition of BJP votes strengthened the TDP’s position among the upper castes and the peasant OBCs, besides consolidating its traditional Kamma votes. These gains more than compensated for the loss of the votes of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes owing to the break with the Left parties, and of Muslims, who shifted their allegiance to the Congress(I). Even so, the TDP-BJP combine enjoyed more support than the Congress(I) did among adivasis; the TDP’s share of votes of Muslims is one of the highest for any ally of the BJP.

The class profile of the TDP-BJP combine shows an uneasy coming together of the upper classes (who predominantly support the BJP) and the lower classes (who support the TDP). The Congress(I) fared well among the middle class but was squeezed from the upper end by the BJP and the lower end by the TDP. Unlike in Karnataka, the Congress(I) could not reconstruct its base among the poorest sections.

During the campaign, TDP leaders repeatedly claimed that the party enjoyed the overwhelming support of women and young voters. The survey findings do not support this claim. Young voters were equally divided between the TDP and the Congress(I). If anything, the TDP does best among the middle-aged, who perhaps acquired their right to vote about the time the TDP first came to power in dramatic circumstances, in 1983. Similarly, the TDP, which earlier drew a larger share of its support from women than from men, now enjoys about the same proportion of votes across the gender divide. The rural-urban divide does not explain much of the difference, for the TDP enjoys the same lead in both areas. The Left parties have their traditional source of support in the villages.

The survey reveals that as compared to voters in many other parts of the country, voters in Andhra Pradesh are more politicised, more confident, and more attuned to regional politics. At the same time, 75 per cent of TDP voters expressed a preference for A.B. Vajpayee as Prime Minister. About 47 per cent of the voters claimed that they had finalised their voting choice much before the campaign began.